Момент истины. Почему мы ошибаемся, когда все поставлено на карту, и что с этим делать? - Сайен Бейлок (2010)

-

Год:2010

-

Название:Момент истины. Почему мы ошибаемся, когда все поставлено на карту, и что с этим делать?

-

Автор:

-

Жанр:

-

Оригинал:Английский

-

Язык:Русский

-

Перевел:Михаил Попов

-

Издательство:Манн, Иванов и Фербер (МИФ)

-

Страниц:160

-

ISBN:978-5-00057-724-0

-

Рейтинг:

-

Ваша оценка:

Момент истины. Почему мы ошибаемся, когда все поставлено на карту, и что с этим делать? - Сайен Бейлок читать онлайн бесплатно полную версию книги

57. Monastersky R. Studies show biological differences in how boys and girls learn about math, but social factors play a big role too // Chronicle of Higher Education, 2005. March 4. Vol. 51.

58. Дополнительно см.: Spelke E. S. Sex differences in intrinsic aptitude for mathematics and science? A critical review // American Psychologist, 2005. Vol. 60. Pp. 950–958.

59. Gallagher A., DeLisi R. Gender differences in Scholastic Aptitude Test — Mathematics problem solving among high-ability students // Journal of Educational Psychology, 1994. Vol. 86. Pp. 204–211.

60. Fennema E., Carpenter T., Jacobs V. et al. A longitudinal study of gender differences in young children’s mathematical thinking // Educational Researcher, 1996. Vol. 27. Pp. 33–43.

61. Butler L. Gender differences in children’s arithmetical problem solving procedures. Unpublished M.A. thesis, University of California at Los Angeles, 1999 // Association for Women in Mathematics president Cathy Kessel’s talk at the MER-AWM Session at the 2005 Joint Mathematics Meetings.

62. Atkinson R. C. Let’s step back from the SAT I // San Jose Mercury News, 2001. February 23 //

63. Spencer S. J., Steele C. M., Quinn D. M. Stereotype threat and women’s math performance // Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 1999. Vol. 35. Pp. 4–28.

64. Дополнительно см.: Steele C. M. A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance // American Psychologist, 1997. Vol. 52. Pp. 613–629; Schmader T., Johns M., Forbes C. An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance // Psychological Review, 2008. Vol. 115. Pp. 336–356.

65. Krendl A. C., Richeson J. A., Kelley W. M., Heatherton T. F. The negative consequences of threat: A functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation of the neural mechanisms underlying women’s underperformance in math // Psychological Science, 2008. Vol. 19. Pp. 168–175. См. также: Beilock S. L. Math performance in stressful situations // Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2008. Vol. 17. Pp. 339–343.

66. Levine S. C. et al. Socioeconomic status modifies the sex difference in spatial skill // Psychological Science, 2005. Vol. 16. Pp. 841–845.

67. Thurstone T. G. PMA readiness level. Chicago: Science Research Associates, 1974. Приведено с разрешения.

68. В 2001 г. 90% всех комплектов Lego, проданных в США, предназначались для мальчиков. См.: Mattel sees untapped market for blocks: Little girls // Wall Street Journal, 2002. June 6. Более того, как сообщала Wall Street Journal 24 декабря 2009 г., Lego практически отсутствуют на рынке игрушек для девочек:

69. Hassett J. M., Siebert E. R., Wallen K. Sex differences in rhesus monkey toy preferences parallel those of children // Hormones & Behavior, 2008. Vol. 54. Pp. 359–364.

70. Wallen K. Hormonal influences on sexually differentiated behavior in nonhuman primates // Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 2005. Vol. 26. Pp. 7–26.

71. Connellan J. et al. Sex differences in human neonatal social perception // Infant Behavior & Development, 2000. Vol. 23. Pp. 113–118.

72. Дополнительно см.: Spelke E. S. Sex Differences in intrinsic aptitude for mathematics and science? A critical review // American Psychologist, 2005. Vol. 60. Pp. 950–958.

73. Guiso L., Monte F., Sapienza P., Zingales L. Culture, gender, and math // Science, 2008. Vol. 320. Pp. 1164–1165.

74. Mattel says it erred; Teen Talk Barbie turns silent on math // New York Times, 1992. October 21 //

75. Figlio D. N. Why Barbie says ‘Math is Hard’ // Working Paper, University of Florida, December 2005.

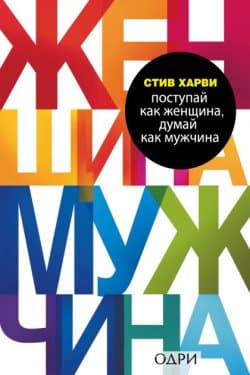

Поступай как женщина, думай как мужчина. Почему мужчины любят, но не женятся, и другие секреты сильного пола Стив Харви

Поступай как женщина, думай как мужчина. Почему мужчины любят, но не женятся, и другие секреты сильного пола Стив Харви

Компаньон Кристина Гедони

Компаньон Кристина Гедони

Тезаурус вкусов 2. Lateral Cooking Ники Сегнит

Тезаурус вкусов 2. Lateral Cooking Ники Сегнит

Правила развития мозга вашего ребенка. Что нужно малышу от 0 до 5 лет, чтобы он вырос умным и счастливым Джон Медина

Правила развития мозга вашего ребенка. Что нужно малышу от 0 до 5 лет, чтобы он вырос умным и счастливым Джон Медина

Меня никто не понимает! Почему люди воспринимают нас не так, как нам хочется, и что с этим делать Хайди Грант Хэлворсон

Меня никто не понимает! Почему люди воспринимают нас не так, как нам хочется, и что с этим делать Хайди Грант Хэлворсон

Здоровое питание в вопросах и ответах Патриция Барнс-Сварни, Томас Сварни

Здоровое питание в вопросах и ответах Патриция Барнс-Сварни, Томас Сварни

Пир теней

Пир теней  Князь во все времена

Князь во все времена  Когда порвется нить

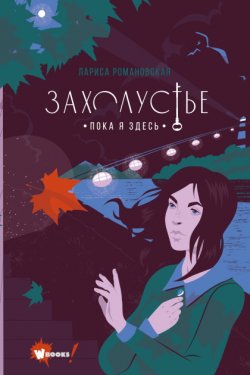

Когда порвется нить  Пока я здесь

Пока я здесь